Welcome to USA Information Course

About the United States of America

American symbols are recognized the world over. The Statue of Liberty, the White House, and the Bald Eagle are just some of the iconic images that may come to mind when students think of the United States of America (also known as the US or America).

Indeed, the US means many things to different people. For some, it is an economic and political powerhouse and an influential player on the world stage; for others, it is defined by its entertainment industry – Hollywood films and the bright lights of Broadway. And for years, many have seen it as the land of opportunity, a destination for immigrants seeking new freedoms and wealth. But the US is much more than its symbols and stereotypes. For international students, the US education system offers world-renowned educational opportunities of all shapes and sizes. Students can choose from a variety of excellent education institutions in cities and towns across the country. They can experience American college life in a nation that is known for its ethnic and geographic diversity, while discovering the sights, sounds, and tastes of the US.

Five Quick Points About the U.S.

- World’s most popular destination for international students

- Third-largest country in world in terms of size and population

- The largest economy in the world according to nominal GDP and one of the most technologically advanced

- Home to some of the highest-quality educational institutions in the world, many with cutting-edge technological resources

- Huge range of educational options: some are broadly focused, some are employment-focused and some are niche (e.g., arts, social sciences, technical)

Location and Geography

The United States of America (also referred to as the United States, the U.S., the USA, or America) borders Canada to the north, Mexico to the south, the North Atlantic Ocean to the east and the North Pacific Ocean to the west. At roughly 9.8 million square kilometres, the U.S. is the world’s third-largest country in size and population and one of the most ethnically diverse and multicultural nations.

The U.S. consists of 50 states (48 continental plus Alaska and Hawaii), a federal district, Washington D.C., and small territories in the Pacific and Caribbean. The capital city is Washington, D.C.

Climate

With its large size and geographic variety, the U.S. includes most climate types from the tropical atmosphere of Hawaii and Florida to the semi-arid Great Plains; from the arid Mojave Desert to the snow-capped Rocky Mountains, and the cold Arctic climate of Alaska. Because of the climate, the ecology in the U.S. is extremely diverse, with abundant flora and fauna and amazing natural habitats for nature-inspired visitors to explore.

History and Population

The United States’ earliest settlers were aboriginal natives (now referred to as Native Americans). The British then began settling on the east coast and eventually established 13 colonies. These colonies declared their independence in 1776 from Britain as a result of the American Revolution.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 officially recognised the United States of America as a sovereign nation, and the U.S. Constitution was signed in 1787. The U.S. went on to become a superpower in the 20th century, and it is one of the world’s most influential nations.

Today, the population of the U.S. is just over 334 million. It is ethnically and culturally diverse, thanks to a long history of immigration, with Caucasians comprising 70% of the population, Hispanics or Latinos comprising 17%, African-Americans constituting 13%, Asians comprising 4%, and indigenous native Americans comprising 1%.

English is the most widely used language, followed by Spanish.

Society and Culture

A common metaphor used to describe American culture is “the melting pot,” which means that a variety of ethnicities and nationalities are represented in the population and blend to form a common culture. While it is true that there is a strong sense of “Americanness” among the population, most would agree that there are still very distinct sub-cultures, especially along ethnic lines (e.g., Hispanic or Latino).

The United States is a secular country, with a core principle being the separation of church and state and the freedom for individuals to worship as they choose. Another distinctive factor is freedom of expression ensuring individuals the right to express themselves without fear of government reprisals. These individual freedoms help to shape a culture where an individual’s interests and skills can be more important than family or connections in the marketplace – at least relative to other countries.

Sports are quite popular in the United States. American football, baseball, and basketball represent the most successful professional franchises, while soccer is popular as a youth team sport. University sports, especially American football and basketball, are also very popular. Elite university football programs, for example, may draw regular crowds of 75,000.

Economy

The U.S. is the largest economy in the world (with China tying or even exceeding it on some measures), and one of the most technologically advanced. Its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023 was roughly $27.94 trillion. American firms are at or near the forefront of technological advances, especially with regard to computers and medical, aerospace, and military equipment.

The currency is the U.S. Dollar ($).

Government

The U.S. is a federal republic with a strong democratic tradition founded on the concept of local control. The federal government shares power with the local governments in each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the territories, and multiple counties, cities, and towns.

At both the federal and local levels, there are three branches of government: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial, where each has authority over different governmental functions in a system of checks and balances. The U.S. legal code is based on English common law (except in Louisiana, which is still influenced by the Napoleonic code).

The Structure of the US Education System

Focus Questions:

- How old are most students when they enter a US kindergarten school?

- What are the types of degrees offered at colleges and universities?

- What are some of the questions international students should ask when deciding which program and school to study at in the US?

- What is the difference between an associate degree and a four-year degree?

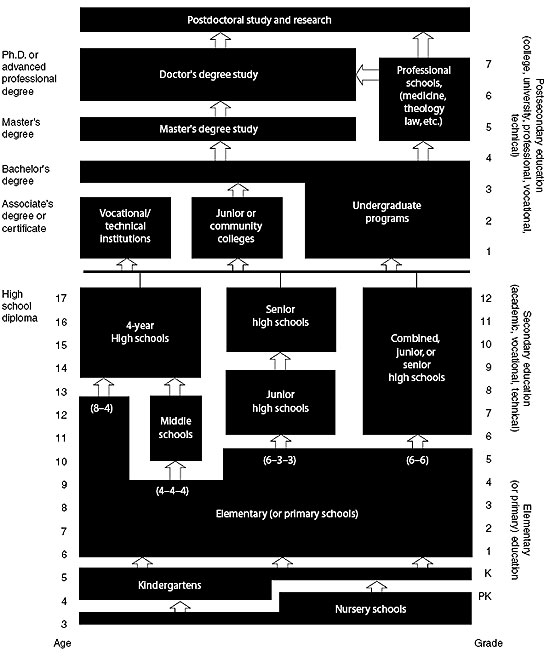

The US education system may be organized very differently from the system in the home countries of international students. Reflected in a chart, it looks like this, complete with pathways between levels:

Pre-School and Kindergarten

American students begin either in preschool or kindergarten for one to three years before progressing to elementary (primary) school. In most states, the age at which a child must start school is six.

Most school districts offer a free year of kindergarten before the starting year; in most cases, children must be five years of age to enter kindergarten. If you are counseling a family planning to have a child under the age of six attending school in the US, make sure to ask the kindergarten schools under consideration about their cut-off birth dates for turning five, as this varies by school district.

Elementary (Primary) and High School (Secondary School)

Children attend elementary (primary) school for varying amounts of time. In most cases, they attend elementary until Grade 6. They then progress to one of the following: a junior high school for two years, a combined junior/senior high school (generally Grades 7–12), or a four-year high school. Please note that high schools can also be called secondary schools.

School-aged students in the US have the option of going to public schools (free) or to private schools (where they must pay tuition or be on scholarship). The vast majority (88%) attend public schools; nation-wide, 9% attend private schools, but this percentage is much higher in some regions and cities, and among Caucasian Americans. Three percent are home-schooled, in which case parents and/or caregivers provide education to children provided their practices meet the education laws of the state.

International students tend to attend K-12 private schools at a much higher rate than public schools, especially because public high school schools allow international students to study for only one year. Private schools have no such limit.

Graduating High School

There is no federally set national examination determining whether a student has successfully graduated high school in the US. However, as of this writing, 25 states require that students take a high-school exit examination for graduation, and three additional states have legislation that will see such exams required in the future.

Whether or not a national examination is used in assessment, American high schools issue high-school diplomas to students who have completed their curriculum.

As we have discussed, because different states and school districts determine what is taught in schools and how, the courses that must be completed to earn a high-school diploma will vary from one school and state to another.

American students normally graduate high school at age 17 or 18.

Post-secondary Options

The US offers a wide variety of higher education options for the diverse requirements and goals of domestic and international students. This variety encompasses:

- Types of institutions (e.g., private vs. public, academic vs. vocational, etc.)

- Length of programs (e.g., one year, two years, four years, etc.)

- Levels (e.g., associate, bachelor’s, master’s, post-graduate)

- Types of credential (e.g., non-degree, degree, micro-credential)

- Delivery models (e.g., online, hybrid, in-person)

- Tuition fees (from very affordable to extremely expensive)

- Location of institutions (e.g., urban vs. rural, west vs. east, etc.)

The US government notes that there are currently:

- 124,000 public and private schools in the US;

- Over 2,000 postsecondary non-degree career and technical schools (CTE);

- Over 4,000 degree-granting institutions of higher education.

They explain: “Of the higher education institutions, over 1,600 award associate degrees and some 2,400 award bachelor’s or higher degrees. Over 400 higher education institutions award research doctorates.”

Flexibility in the System

International students may decide to begin at one type of institution (for example, a community college) and then move to another institution or level. Many higher education institutions have agreements that allow students to transfer credits achieved at a two-year institution to a degree program at a four-year institution. Students who choose to “mix and match” their study programs often do so because it can be more affordable.

Important note for agents: Not all two-year programs lead seamlessly (through transfer credits) to four-year institutions. It is important to ask if there are agreements in place for international students interested in this kind of progression.

Is there a difference between a “college” and a “university”?

In the US, the terms “college” and “university” often – but not always – refer to the same kind of higher education institution (HEI), and as pathway provider Shorelight points out:

“Some are even called institutes (e.g., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, California Institute of Technology). Within larger universities in the United States, there are different colleges or schools that represent different academic areas of study (e.g., College of Engineering, School of Business).”

WENR concurs but adds a bit more clarification on characteristics a “university” must have but that a “college” may or may not offer:

“There are no nationally standardized definitions of “university” or “college,” and the name of an institution alone may not indicate exactly what type of institution it is. That said, a university, at minimum, offers bachelor’s programs and at least some master’s programs.”

The term “university” may also indicate that an HEI is relatively more research-intensive (e.g., with more postgraduate degrees) than other types of post-secondary education.

Types of College/University

One way of understanding post-secondary options in the US is to look at how they are funded.

Public universities (also known as State universities) receive at least some of their funding from the state government. Many belong to a state university system, which is a larger group of public universities spread throughout a US state that are connected in some ways through administrative functions but that operate separately from each other. Examples are State University of New York (SUNY), City University of New York (CUNY), and University of California (UC).

Community colleges are also supported by public funding, and they mainly specialize in offering two-year degree programs (associate degrees).

Private universities receive most of their revenue through students’ tuition fees, which are often higher than those charged by public universities. These institutions are often highly ranked and with very selective admissions requirements, include Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Harvard, and Yale. For more examples, please click here.

Liberal arts colleges offer mostly (though not exclusively) undergraduate courses focus on teaching undergraduate-level courses in the liberal arts and sciences (although some also offer graduate-level programs and more vocational subjects such as medicine, business administration or law).

For-profit private universities and colleges. Unlike other types of university, for-profits operate as business ventures, aiming to make money for their shareholders as well as providing a good education for their students.

Carnegie Classification System

A useful tool for understanding the different types of higher education institution (HEI) that international students can attend in the US is the Carnegie Classification System:

- Doctoral universities: HEIs that awarded at least 20 research/scholarship degrees in the past year that are not professional practice doctoral-level degrees (such as the JD, MD, or PharmD).

- Master’s colleges and universities: HEIs that awarded at least 50 master’s-level degrees and fewer than 20 doctoral degrees during the past year.

- Baccalaureate colleges: HEIs where at least 50% of degrees were awarded in the past year at the bachelor’s level or higher, comprising fewer than 50 master’s degrees or 20 doctoral degrees. In other words, bachelor’s degrees are these institutions’ primary focus.

- Baccalaureate/associate’s colleges: HEIs that mostly award associate degrees but that also have at least one baccalaureate (four-year) degree program. Associate degrees must make up at least 50% of all degrees awarded in the past year.

- Associate’s colleges: HEIs at which the associate degree is the highest level of degree awarded to students.

- Special focus institutions: Institutions where a single field or set of fields (e.g., music, art) dominate the focus of the institution and degrees awarded are linked to this field. These include

- Faith-Related Institutions, Medical Schools & Centers, Other Health Professions Schools, Engineering Schools, Other Technology-Related Schools, Business & Management Schools, Arts, Music & Design Schools, and Law Schools. For more on such institutions, please click here.

- Tribal colleges: International students are not eligible to attend these colleges because they are reserved for Native (Indigenous) Americans.

As well as understanding the Carnegie Classification System, agents should also know that there are many excellent vocational programs in the US delivered through Career and Technical Education (CTE) schools and community colleges. This is increasingly important because research shows that there is growing interest among students across the world in shorter, practical programs.

Five Important Facts About the Post-Secondary System In the US

- There are both public and private colleges/universities in the US. Most of these are operated by the states and territories.

- As noted earlier in this section, “college” and “university” are often used interchangeably, but they sometimes do mean different things to different people. For example, a university can sometimes indicate a more research-oriented orientation than a college, and sometimes universities are broken down into different “colleges,” whereby “college” indicates a unit or sub-section of the university. Still, it is important that agents research a college/university thoroughly to understand its educational approach and range of programs, as the word “college” or “university” in a name does not always mean the same thing.

- Top-notch higher education institutions in the US come in all shapes, sizes, and types. Successful alumni graduate from community colleges, liberal arts colleges, research-oriented universities, public and private institutions – not just the most elite, Ivy-League schools. Excellent programs can be found across the country.

- Quality assurance and accreditation for institutions and programs in the US is carried out by private, non-governmental organizations. The US Department of Education provides oversight of these accrediting organizations. There are 19 recognized organizations that provide regional or national accreditation for institutions, and 60 that provide accreditation for individual programs. To obtain an F-1 visa, students must enrol in an accredited institution. Agents must make sure that an institution and program is accredited before recommending it to students for the purposes of quality control. For more on why this is, and for The Council of Education (CHEA) database providing information about over 8,200 institutions and over 44,000 programs in the US, please click here. [ https://www.chea.org/about-accreditation ]

- Each HEI will have different admissions practices. Generally, shorter degree programs and certificates have lower admission standards: some even offer “open admissions” in an effort to be as inclusive to every type of student as possible. However, as the need for professional and technical skills grows in economies across the world, there are increasingly more competitive admissions policies for in-demand fields such as engineering, nursing, and other healthcare fields.

Accrediting Agencies

Focus Questions:

- Are institutions obligated to obtain accreditation?

- Why would they seek it out?

- Name two things that suggest a school may be a “diploma mill”?

Agents need to know whether a US higher education institution, traditional or online, conforms to high and official standards of educational quality. Whether a school is accredited by a recognized and US-government approved accrediting agency is the main way of finding out.

As the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) says, “In the United States, accreditation is a major way that students, families, government officials, and the press know that an institution or program provides a quality education.” Further, CHEA advises that,

“In the US, colleges and universities are accredited by one of 19 recognized institutional accrediting organizations. Programs are accredited by one of approximately 60 recognized programmatic accrediting organizations.”

The CHEA “Database of Institutions and Programs Accredited by Recognized United States Accrediting Organizations” contains information about over 8,200 institutions and over 44,000 programs in the US, with links to the websites of these institutions.

AccreditedSchoolsOnline.org says,

“If a school is accredited by an organization not recognized by the CHEA or US Department of Education, it’s almost as if the school isn’t accredited at all. Just as accreditation ensures a school isn’t a degree mill, recognition ensures an accrediting agency isn’t an accreditation mill. These layers of protection for students help ensure their degree is much more than a simple piece of paper.”

Institutions are not required to seek accreditation, but most do to show they meet the standards of their competitors.

Knowing whether or not an institution is accredited is important because:

- Credits are more transferable between accredited institutions;

- Degrees and diplomas from accredited institutions will be recognized not only in the US but also internationally.

AccreditedSchoolsOnline.org notes that international students who attend non-accredited schools (or schools with fake accreditation) “face the possibility of graduating with a degree, diploma or certificate that is practically worthless beyond any personal satisfaction the student may garner from the accomplishment.” They continue: “Given the time and monetary cost of a college education, prospective students must make sure their chosen school and/or program is accredited.”

The US Department of Education lists the following as Functions of Accreditation:

- Verifying that an institution or program meets established standards;

- Assisting prospective students in identifying acceptable institutions;

- Assisting institutions in determining the acceptability of transfer credits;

- Helping to identify institutions and programs for the investment of public and private funds;

- Protecting an institution against harmful internal and external pressure;

- Creating goals for self-improvement of weaker programs and stimulating a general raising of standards among educational institutions;

- Involving the faculty and staff comprehensively in institutional evaluation and planning;

- Establishing criteria for professional certification and licensure and for upgrading courses offering such preparation; and

- Providing one of several considerations used as a basis for determining eligibility for Federal assistance.

IDP India provides this helpful graphic explaining the benefits of going to an accredited school in the US:

Check out the US Department of Education’s list of approved institutional accrediting agencies here. This includes accrediting agencies for professional degrees such as nursing, law, osteopathy, etc.

How to Spot Fraudulent Schools

CHEA provides incredibly important advice for agents and international students who might not be familiar with how to distinguish legitimate versus fraudulent schools. This is their checklist – obviously agents and students should not partner with/enrol in an institution they have reason to believe is a “diploma mill” and should be sure that that the institution has been properly accredited in this database.

If the answers to many of these questions are “yes,” the operation under consideration may be a “mill”:

- Can degrees be purchased?

- Is there a claim of accreditation when there is no evidence of this status?

- Is there a claim of accreditation from a questionable accrediting organization?

- Does the operation lack state or federal licensure or authority to operate?

- Is little if any attendance required of students?

- Are few assignments required for students to earn credits?

- Is a very short period of time required to earn a degree?

- Are degrees available based solely on experience or resume review?

- Are there few requirements for graduation?

- Does the operation charge very high fees as compared with average fees charged by higher education institutions?

- Alternatively, is the fee so low that it does not appear to be related to the cost of providing legitimate education?

- Does the operation fail to provide any information about a campus or business location or address and relies, e.g., only on a post office box?

- Does the operation fail to provide a list of its faculty and their qualifications?

- Does the operation have a name similar to other well-known colleges and universities?

- Does the operation make claims in its publications for which there is no evidence?

K-12 Schools in the US

Focus Questions:

- How many international students are studying at US high schools?

- What is one reason that parents of international students are more likely to send their child to a private rather than public high school?

- What is one reason that families around the world send their children to US high schools?

In 2020, there were close to 60,000 international students in K-12 education in the US, more than 90% of whom were enrolled at the secondary school level (i.e., high school).

The nationalities most represented among international students at this school level are China (more than 40%), as well as South Korea, Japan, Germany, Vietnam, Spain, Italy, Brazil, Mexico, and Canada.

In the US, international students can only attend public schools at the Grade 9–12 level, but private K-12 schools can accept students from kindergarten through to Grade 12.

The majority of international secondary students in the US are on F-1 visas (68% in 2019) while about a third are on J-1 (exchange) visas. Most international students on J visas are from Europe, while most F-1 students are from Asia. In 2019, German, Spanish, and Italian students composed 44% of all J‐1 secondary student visas.

All K-12 schools in the US, public and private, must be registered with the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) to be able to accept international students. Nearly 3,000 K-12 schools now accept international students.

The IIE reports that most international secondary students in the United States ultimately seek to enroll in higher education, and that,

“The experience of learning in U.S. classrooms, immersion in English-language instruction, and adjusting to U.S. life prior to higher education can ease the transition of international students moving from U.S. high schools to higher education.”

More than 90% of international students in the US for secondary school studies attend private high schools, and more than half of these students attend religiously affiliated schools. Private schools are the first choice for several reasons, including the fact that US law prevents international students on F-1 visas to study for more than one year at a public high school. Students can then transfer to a private high school if desired, but it is naturally easier to enroll in one school for the duration of studies.

Evaluation in US High Schools

Focus Questions:

- How are students’ grades determined in US high schools?

- What standardized tests are commonly taken in Grade 11?

- What is a GPA?

Students are evaluated through the year on their performance and progress, and report cards are sent home to parents periodically through the year so they can see how their children are doing academically.

Grading scales differ from school to school, but the most common scale is A through F, where A is the highest level of performance and F is a failing grade based on a scale of 0–100 or a percentile.

Beginning in 11th grade, most students with intentions to go on to higher education take standardized tests: the SAT and ACT are the most common and students may take one or both. There are also SAT subject tests that some students decide to take to bolster their college applications.

At the end of high school, students receive a Grade Point Average (GPA), which is a cumulative average score derived from the sum of the student’s tests, exams, essays, projects, assignments, participation in class activities and group work, and attendance record. Students can also be ranked in their class according to their GPA.

Most four-year universities evaluate students according to “minimum GPA” (meaning they will accept only students who meet this minimum threshold. Minimum GPAs are usually no lower than 2.0 and become higher the more selective a university is in its admissions. However, some students who do not meet minimum GPA requirements can gain admission in some cases if they show outstanding performance in other areas (e.g., athletics) or if they achieve excellent scores on standardized tests like the ACT and SAT.

The US K-12 Public School System

Focus Questions:

- Is tuition at public schools always the same or can it vary?

- Which level of government provides most funding to K-12 schools?

K-12 public schools get most of their funding from state and local budgets, while the federal government provides about 10% of schools’ budgets in the form of grants, some of which is tied to their performance on standardized tests, via the federal No Child Left Behind act.

Individual states and local school districts control most of the decision-making at the K-12 level.

Different states vary in how they share educational decision-making with local school districts, but together they decide on what subjects will be taught, how they will be taught, which books will be used, the school calendar, supports for special students (e.g., learning or physically challenged), how students are evaluated, and graduation requirements for different grades.

Like private schools, public schools in the US are accredited and students should only attend accredited schools.

Tuition at public schools ranges from $3,000 to $10,000 per year.

The class ratios are generally 18–25 children to one teacher. The teacher may also have the support of a teacher’s aide and/or a special education teacher (who helps with integrating developmentally or physically challenged children into the classroom).

Rules for International Students Attending Public High Schools in the US

Focus Questions:

- How many years can F-1 students study at a public high school?

- How many years can J-1 students study at a public high school?

- Do J-1 students pay tuition? Do F-1 students?

- Do F-1 students have any limitation on where in the US they can study?

- What is the minimum age at which J-1 students can begin studies in the US?

- Can J-1 students receive a high school diploma from a US school? Can F-1 students?

International students who want to attend public high schools will apply either for an F-1 or J-1 visa. Both classes of visa restrict study at a public high school to one school year. (By contrast, there is no time constraint for K-12 students on F-1 visas studying at private K-12 schools in the US).

The Department of Homeland Security states that,

“F-1 students attending an SEVP-certified public secondary school must compensate U.S. taxpayers by paying the full, unsubsidized per capita cost of attending school for one year in that location. Payment of this cost and the I-901 SEVIS Fee must occur before the prospective student applies for an F-1 or M-1 visa.”

There is no exception to this rule.

J-1 students attending public high schools:

- Must be between the ages of 15 years and 18.5 years of age on their first day of school in the US.

- Must live with local homestay families.

- Must return to their home country at the end of the school year and are usually excluded from returning to the US on any kind of student visa for at least two years.

- Can apply only through a specially licensed US organization that can only place a limited number of students each year; getting accepted to this program is a very competitive process that must be started almost one year in advance.

- Do not pay for school tuition fees because the J-1 program is subsidized by the government to further cultural exchanges between the US and the student’s home country. The main costs are airfare and placement and monitoring fees that students will pay to the J-1 placement organization.

- Usually do not have a choice on which location or school they will attend.

- Cannot graduate or receive a high school diploma, regardless of the number of credits they have earned.

In addition:

The J-1 program application process is somewhat complicated and the rules are very strict. F-1 visa programs, on the other hand, require a much simpler application and fewer supporting documents. This allows students to begin the application process earlier, and get accepted to the school of their choice much sooner.

F-1 students attending public high schools:

- Can live with local homestay families or live with non-immigrant relatives in the US while they study.

- May continue, after their year at a public high school, to a private high school or begin their university education without having to change their visa status or return to their country.

- Must pay school tuition and room and boarding fees with their own family funds since F-1 programs are not sponsored by the US government.

- Can choose which state, city and school they would like to attend depending on their qualifications and space availability.

- May be able to graduate and receive a diploma from the high school they attend (if they are accepted to Grade 12 and have enough credits to graduate within one school year).

For more information on J-visas at the secondary school level, please visit this US State Department webpage. For F-visas at this level in the public system, please visit this webpage.

US K-12 Private Schools

Focus Questions:

- What are some of the reasons that parents choose to send their children to private schools, despite the higher cost?

- What are some of the features private schools are more likely to have than public schools?

In the US, some families with abundant resources or financial aid choose to send their children to a private school to increase the chances their children will receive an excellent education. Many parents of international students also decide to send their children to an American private school, often with the hope that it will help to set them up for a place in a good American college or university.

There are roughly 35,000 private schools in the United States, serving more than 5 million students and enrolling about 10% of all pre-kindergarten to Grade 12 students in the country. More than three-quarters of students in private schools attend religiously affiliated schools. Almost 9 in 10 private schools have fewer than 300 students.

In some ways, there is more variety in the US K-12 private school system than in the public system, for the following reasons outlined by PrivateSchoolReview.com:

“While private schools are subject to all applicable local, state and federal laws and regulations governing the business side of things, private schools handle educational matters according to their educational philosophy and the wishes of their families and students. The essence of a private school is its curriculum and how it chooses to teach that curriculum is a matter which it decides in consultation with its clientele. The market drives private schools.”

The US Department of Education has this to say about US private schools:

- Private school students generally perform higher than their public-school counterparts on standardized achievement tests;

- Private high schools typically have more demanding graduation requirements than do public high schools;

- Private school graduates are more likely than their peers from public schools to have completed advanced-level courses in academic subject areas;

- Private school students are more likely than public school students to complete a bachelor’s or advanced degree by their mid-20s.

The National Center for Education Statistics’ National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests the knowledge and skills of the nation’s students in grades 4, 8, and 12. Routinely, the scores of students in private schools are much higher than the national average.

Many foreign-based families decide to send their children to private high schools in the US to prepare them for entrance to a US college, especially if the college is competitive and/or elite. A US World News Report lists these benefits for international students attending high school in the US:

- Improved English skills

- Easier navigation of the US college system

- College readiness

- Social skills

Many international students also take English-language courses during the summer break (i.e., outside of the normal academic year). The US government provides this guidance for visa rules and processes around summer language programs for K-12 students.

To attend a private school in the US, students must pay tuition. This is in large part linked to the fact that private schools are not funded by the government. This tuition can vary greatly, ranging from $10,000 to $40,000 to more for private boarding schools (which will be covered in an upcoming section). Beyond tuition, there will be additional fees as well which families must factor in to get to the true cost of a private school education. Financial aid for international students may be available at some private schools.

Private schools are able to charge so much tuition because of the extra resources, high quality of teachers, low student-teacher ratios, excellent facilities (e.g., sports, arts, computer), and extra-curricular opportunities they provide students.

Here is a link to a private school search for the US (and Canada).

VERY IMPORTANT FOR AGENTS: Because space at private schools is often limited, not all students who apply will be admitted. The application process for private schools can take months. Find out from the schools your students’ families are considering how far in advance to begin, and what documents and other steps are required.

Rules and Application Procedures for International Students

International students wishing to study in the US at the K-12 level must attend a school that is certified by the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP). These are the only schools authorized to accept international students. You can use this page to make sure the school under consideration is certified.

Because space at private schools is often limited, not all students who apply will get in. The application process for private schools must start much earlier and can take months. Find out from the schools themselves how far in advance to begin, and what documents and other steps are required.

Most private schools, especially at the high-school level, will ask that prospective students take one or more standardized admissions tests. These might include the SSAT (Secondary School Admission Test), the ISEE (Independent School Entrance Examination), the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language), or the school’s own tests. Students should begin studying for these tests about six months before actually taking them. The tests are meant to ensure the school and accepted students are a good match, and to place students properly in classes and provide them with the right supports (for example, English-language help).

Please Note: acceptance into a SEVP-certified school is the first step in an international student’s process to study in the US – before applying for a student visa.

For more information on how international students should apply for a visa to attend either a private school or boarding school, this PrivateSchoolReview.com article is helpful.

K-12 Boarding Schools in the US

Focus Questions:

- Why might the residential feature of boarding schools be helpful for international students?

- What is the admissions application that might be very helpful for students applying to boarding schools?

BoardingSchools.us defines a boarding school as “a school where pupils reside during the semester.” They continue: “Students are provided with food and lodging in addition to their education, but a boarding school has much more than that to offer to students and their families. Traditionally, boarding schools provide an education based on small class sizes, high standards of academic excellence, and cultural diversity.”

At a boarding school, students live on the school’s premises as they study. Many boarding schools enrol both day students (who leave after school is done for the day to their houses) and “boarders” who stay on the premises for longer periods of time: Full-term boarders go home at the end of an academic year, semester boarders go home when the academic term is over, and weekly boarders go home for weekends. International students tend to be longer-term boarders rather than day or week students.

International students make up about 15% of all students in American boarding schools.

Teachers and staff sleep on the premises so they are quickly available to students at all times, even after school. Students receive all their meals from the school.

Most boarding schools charge tuition and fees for room and meals, and the typical cost ranges from $15,000 to over $65,000 per academic year. WorldScholarshipForum.com lists several scholarship programs for international students wanting to go to a boarding school.

Association of Boarding Schools (TABS) research has found that boarding school students are more likely to find academics to be challenging (91%) than private school students and public school students (71% and 50% respectively). Boarders tend to have more homework and more extra-curricular activities like sports and music.

They are often diverse: more than half of boarders reported that their school is “ethnically and racially diverse,” compared to 19% of private day students and 39% of public school students.

US K-12 boarding schools are very popular destinations among families overseas who want to see their children receive an excellent K-12 education and in many cases, progress to a quality American college or other post-secondary institution. Some families consider benefits of boarding schools to be:

- The personal development and confidence that comes from the challenge and adventure of living away from home with an eclectic mix of other students;

- The close friend networks that can be formed at boarding school can last a lifetime;

- Small school and class sizes and close interaction between teachers and students;

- Specialty programs available at many boarding schools (e.g., dance, filmmaking, visual arts).

TABS found that fully 87% of boarding school graduates said their school prepared them well academically for university life. By comparison, 39% of public school students and 71% of private day school students reported the same.

BoardingSchools.com lists four basic steps to applying to a boarding school in the US:

- Complete the application forms which the school has on its website.

- Complete the common application which you can find on the SSAT website.

- Complete the common application which you can find on the TABS website.

- Complete the paper application forms which you have either downloaded or received from the school.

They offer this tip for international students:

If you are an international student, read the requirements for international students on each school’s website. These requirements will differ from school to school, so do not assume that what one school asks for applies to other schools. You will have to take the TOEFL examination. Allow adequate time to prepare for and take this examination. The school will give you the documents which you need to apply for an F-1 visa. Apply for the visa as soon as you can. Some US consulates are booked months in advance for visa interviews. Bear that in mind as you apply to American schools.”

For a list of boarding schools in the US, please check this BoardingSchools.com link.

Professional Education and Training Schools

In this section, we will look at post-secondary schools in the US that offer career and technical education. Career-oriented education is also available at the secondary school level but we will limit our focus to the post-secondary level in this section.

These schools are known by several names. These include Professional Education and Training Schools (PET), Career and Technical Education (CTE), or Vocational Education and Training (VET). We will use the second term and its abbreviation, CTE.

CTE schools provide the majority of technical and professional training in the US (more than half), while two-year community colleges provide the rest.

Private CTE schools make up only a small proportion of international student enrolments in the US, but this may grow as the need for career-specific skills and training increases in the global economy.

We will begin by outlining what is meant by “professional education and training,” then go into more detail about the kinds of schools and programs available.

Focus Questions:

- What is the main goal of every CTE program – that is, what does it prepare students for?

- What are the two varieties of CTE programs, as determined by what students can do with their credentials?

There are many ways to understand the CTE sector in the US – and the understanding is evolving as the importance of skills requiring formal, specialized training rises in the US economy. The following is the American government’s current position on CTE:

“CTE represents a critical investment in our future. It offers students opportunities for career awareness and preparation by providing them with the academic and technical knowledge and work-related skills necessary to be successful in post-secondary education, training, and employment. Employers turn to CTE as an important source of talent that they need to fill skilled positions within their companies.

Effective, high-quality CTE programs are aligned not only with college- and career-readiness standards, but also with the needs of employers, industry, and labor. They provide students with a curriculum based on integrated academic and technical content and strong employability skills. And they provide work-based learning opportunities that enable students to connect what they are learning to real-life career scenarios and choices.

The students participating in effective CTE programs graduate with industry certifications or licenses and post-secondary certificates or degrees that employers use to make hiring and promotion decisions.

These students are positioned to become the country’s next leaders and entrepreneurs. And they are empowered to pursue future schooling and training as their educational and career needs evolve.”

— The US Department of Education

The simplest way of describing what CTE education is designed for is to say that a CTE course of study prepares students for a specific job in the economy. For example: licensed practical nurse, automotive technician, or IT technical support specialist.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) states that these are the career fields covered by CTE:

- Agricultural and natural resources

- Business support, management, and finance

- Communications

- Computer and information sciences

- Construction

- Consumer services

- Education

- Engineering and architecture

- Health sciences

- Manufacturing

- Marketing

- Public, social, and protective services

- Repair

- Transportation

Other factors to consider about CTE schools:

- They can be multi-disciplinary (that is, teaching many subjects) or single-focus (for example, a school of acupuncture or cosmetology); the latter (single-focus) often have smaller student populations.

- They differ from community colleges mostly because they are often more focused on “training” than on “education” – they also tend to be more specialized, offering a smaller range of courses.

- They are very hands-on and practical, with very strong teaching and other ties to actual industry.

- Their programs can be either “terminal” (i.e., offer a stand-alone, non-transferable certificate or associate degree) or “transfer” (where a student can put credits obtained in a course toward another degree).

- They can be anywhere from a few months-long in duration to four-years-long, and they can be roughly divided into less-than-two-year institutions and two-year institutions;

- They tend to attract more certificate-seeking students than associate degree-seeking students; the latter tend to enroll at community colleges.

Of the millions of CTE credentials awarded to students every year in the US, most are certificates, but a significant proportion are associate degrees.

A great video explaining CTE in the US can be found here on the AppliedEducationSystems.com website.

How CTE Schools are Governed, Funded, and Accredited

Focus Questions:

- Are CTE schools generally more expensive for international students than community colleges?

- Is tuition at CTE schools fixed or variable?

Each US state has one or more state directors for CTE, responsible for overseeing the state’s secondary and post-secondary CTE systems.

Private CTE schools tend to receive the bulk of their funding via student tuition and, indirectly, from federal funding directed almost totally to domestic students to help these students afford their programs. Though students at CTE schools often receive more financial aid than at community colleges, the net cost of their program is also often higher than if they were attending a community college. Tuition costs at a private CTE are highly variable due to the scope of their specializations, equipment, and duration. It is impossible to estimate; agents will have to check with individual schools for this information.

From The Federal Trade Commission:

“Licensing is handled by state agencies. In many states, private vocational schools are licensed through the state Department of Education. Ask the school which state agency handles its licensing.

Accreditation usually is through a private education agency or association that has evaluated the program and verified that it meets certain requirements. Accreditation can be an important clue to a school’s ability to provide appropriate training and education – if the accrediting body is reputable. You also can search online to see if a school is accredited by a legitimate organization. Two reliable sources to check are:

- Database of Accredited Postsecondary Institutions and Programs, posted by the US. Department of Education.

- Council for Higher Accreditation database.

It is very important to know whether a CTE school with national, as opposed to regional, accreditation, offers degrees that will be accepted at regionally accredited schools or colleges. Regionally accredited schools may not accept transfer credits from nationally accredited schools.

Also check out the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges (ACCSC).

How to Explore CTE Schools and Programs

Focus Questions:

- What kind of information could you learn from a college search website about a CTE school?

- Name five items to check to make sure a CTE school is the right fit for a student.

There is publicly available information that can help when comparing institutions. The Higher Education Amendments in the US require institutions to reveal graduation and employment outcomes to prospective and current students. Colleges generally publish this information on their websites or in brochures.

There are also college search websites, and many of these also publish graduation and/or employment information.

The US Department of Education-sponsored College Navigator provides information on programs, tuition, and fees, accreditation, and graduation rates, among other institution and student characteristics.

For example, we conducted a search for health sciences certificate programs in the US and came upon more than 200 results, which included incredibly detailed information including:

- Credentials awarded

- Campus setting

- Student population

- Faculty to student ratio

- Tuition, living expenses, and financial aid

- Admissions policy

- Accreditation

Another search tool (non-governmental) is College Match which allows you to search by college location, size, gender mix, type of institution, admissions criteria, freshman satisfaction, graduation rate, cost, financial need met, student debt, sports, student background, and academic programs.

There are also:

Evaluating a CTE School

If you have an international student interested in vocational training in the US, a CTE school may or may not be the right fit. Explore also community colleges to see what they have on offer, and when you research CTE schools, complete this checklist:

- Facilities and Equipment: For CTE, the quality of the learning environment and equipment is a huge factor in how good the training can be. Agents should be able to visit in-person to inspect the classrooms and equipment. They should receive ready information about the types of equipment – e.g., computers and tools – teachers are able to use with their students. This equipment should be compatible and current with that used in the given industry.

- Language Support: Can the school support an international student with less than proficient English? At what cost? How?

- Quality of Teachers: How engaged are teachers – and how close are their ties to the industry? Do they still have relevant experience? The quality and experience of teachers is incredibly important in this sector.

- Measures of Success: How successful are alumni? What is the completion rate? The drop-out rate?

- Finances: Ask not just for tuition costs, but every cost that will affect the budget of your international student. In most cases, there will not be financial aid available to international students but ask the school just in case. EduPass offers an excellent resource for investigating possible sources of financial aid for international students in the US.

- Licensing and Accreditation: You will want names and contact information for the school’s licensing and accrediting organizations; follow up with these to determine the quality of the school’s standing. As the Federal Trade Commission says: “Also find out whether two- or four-year colleges accept credits from the school you’re considering. If reputable schools and colleges say they don’t, it may be a sign that the vocational school is not well regarded.”

Community (Two-Year) Colleges

Community colleges are also known as two-year colleges and junior colleges. According to The Department of Homeland Security, a community college can be defined as a “two-year school that provides affordable post-secondary education as a pathway to a four-year degree.” However, this definition is expanding as these institutions are also being seen as very interesting alternatives to classic four-year colleges or institutions. Moreover, some community colleges are offering four-year bachelor’s degrees as well as two-year credentials.

As College Board notes, community colleges “provide a separate type of learning that involves rigorous coursework and preparation for a future profession.”

Agents must be absolutely clear on whether or not a community college program has a “2+2” transfer agreement with other four-year institutions. This information is crucial for many students. At the same time, there are many four-year institutions that evaluate and accept community college credentials and students without 2+2 arrangements in place, so the lack of a 2+2 transfer agreement does not necessarily mean a community college student cannot progress to a four-year institution. This will be expanded upon later in Section 6.1.

Focus Questions:

- What proportion of undergraduate students are in community colleges?

- Are any community colleges awarding bachelor’s degrees?

- On average, how much is tuition (per year) at a community college?

There are currently about 1,000 community colleges in the US, of which the great majority are public and state funded. These two-year colleges enrolled 35% of all undergraduate students in the US in 2019/20 – the proportion is higher when the number of students in four-year bachelor programs offered by community colleges is counted.

The American Association of American Colleges (AACC) explains the role of community colleges like this:

“Community colleges … provide open access to post-secondary education, preparing students for transfer to four-year institutions, providing workforce development and skills training, and offering non-credit programs ranging from English as a second language to skills retraining to community enrichment programs or cultural activities.”

In addition, some community colleges now offer four-year programs, including bachelor’s degrees.

They are very popular institutions for undergraduate studies in the US: as of the 2019/20 school year, approximately 11.8 million students were enrolled in community colleges, 9% of whom were international students.

About 58% of community college programs are for credit, while 42% are non-credit. For international students, of course, non-credit programs will likely not be of interest unless they are designed to help increase English proficiency.

The average annual cost of tuition at a US community college is $3,770, compared with $10,500 for public four-year colleges.

The average age across community colleges is 28; and these institutions are much more diverse in their demographics than traditional four-year universities (i.e., in terms of age, race, educational background, goals, experience).

The most popular fields of study are business/marketing, health professions and related clinical sciences, computer and information sciences, liberal arts, and engineering technologies/technicians. However, there is a huge range of programs available at community colleges. Education USA notes that American community colleges lead the way in educating students in “biomedical technology, biotechnology, robotics, laser optics, internet and computer technologies, and geographic information systems.”

Community colleges tend to offer a broader range of program options than CTE schools do – with both vocational (i.e., career-specific) training as well as broader academics (e.g., marketing and communication). CTE schools, as a refresher, are much more career and/or technical in their orientation.

Community colleges are also known for the transferability of some of their programs – in other words, credits or an entire certificate or a degree from a community college often can be used toward a four-year degree at a college/university. These transfer agreements are most common between community colleges and universities that are geographically close to each other (e.g., the same city or same state). IMPORTANT: This is not true at all community colleges, and transferability may only apply between certain two-year community colleges and four-year colleges/universities. Understanding transfer arrangements is a key task of the agent placing international students at community colleges.

Important for agents will be finding out how much experience a community college has in supporting international students. One clue is whether or not the college has an International Student Office (ISO), but there may be other supports apart from this as well.

Benefits of Community Colleges and Accreditation

Focus Questions:

- Do all community colleges have the same tuition policies for international students?

- What is a 2+2 agreement? Is it more or less expensive than completing all four years at a four-year college?

Why Attend a Community College?

- They can provide an easier transition to the culture of American education for international students. There are lower admission requirements, a greater range of students, and often dedicated staff devoted to helping students with cultural, language, and study challenges. In addition, they often have smaller classes and smaller teacher/student ratios.

- They can allow international students with lower grades/test scores to (a) get into a degree program because of their more open admissions criteria and (b) improve their academic performance to the point they can transfer to a four-year college/university.

- They can often offer robust English-language upgrading courses and tutoring services. What’s more they often require lower (or no) TOEFL scores from international students than four-year colleges/universities, so being highly proficient in English is not as crucial to beginning a course of study. They also generally have good career counselling services, dedicated as they are to helping students find the employment they want.

- Community colleges can offer excellent associate degrees and certificates in their own right (i.e., without an eventual transfer) that provide job-ready and demanded skills in the American and global economy. The facilities and the technology they offer students are in some cases outstanding.

- American community colleges can be a less expensive entry point into American higher education because their tuition rates are much lower at the freshman (1st year) and sophomore (2nd year) level. This is important because many international students are self-funded with limited options for financial aid.

- They can be a less expensive way to obtain a bachelor’s degree (except in cases where students have received a university scholarship). There are many excellent community colleges that have “2+2” transfer agreements with four-year colleges. Attending the first two years of a degree at a community college then transferring for the latter two years to a four-year college/university is almost always less expensive than doing all four years at a college/university.

- Some four-year colleges and universities even offer guaranteed admissions to graduates of the community colleges with which they have transfer arrangements.

Considerations

Though choosing to study at an American community college has many advantages for international students, it is important for the agent to investigate whether the college charges more tuition to international students than to domestic students. This may be quite variable; some states have agreements with countries regarding tuition, some colleges have the ability to waive fees for a certain number of students, and some colleges even charge international students three times more in tuition than domestic students.

Additionally, one obstacle for some international students will be the lack of campus housing at many of these colleges. Only 28% of community colleges offer on-campus housing. In many cases, students will have to arrange for off-campus accommodations. Often, community colleges will offer assistance for international students to find off-campus housing, whether it be an apartment, shared housing, or a host family.

Governance and Accreditation

As with four-year colleges and universities in the US, a board of directors in each state generally governs community colleges. This board is sometimes appointed by the state’s governor.

Accreditation of American community colleges occurs as it does for all colleges and universities in the US, as described in Section 2. As with any school the student is looking into, only American community colleges that are members of a recognized accrediting body should be considered as a valid study option. Check CHEA’s site for a list of community colleges that are accredited.

How to Help International Students Explore Community Colleges in the US

Focus Questions:

- What are three reasons a community college might be a good fit for an international student?

- Could a community college be the only institution an international student would attend in the US (i.e., without transferring to a four-year college?) Why?

Online Resources

Resources include:

- The AACC’s Community College Finder

- The Community College Review

If you are wondering whether a community college or a four-year university is the best option for the students you are counseling, consider this passage from College Board:

“While community colleges typically offer a wide range of benefits for students, this choice may not be the best option for everyone. When weighing the choice between attending a community college and a four-year institution, ask yourself the following questions:

- What do I want to study?

If community college is in your future, make sure to choose a school that offers the degree program you want. These schools have a much more diverse catalogue today, so you can find major areas of study in nearly any field.

- What can I afford?

When finances are tight and you don’t want to graduate from college with a huge amount of student debt, community college can be a good option.

- How important is campus life?

One drawback at many community colleges is the lack of a campus community. Many students at community colleges are adults juggling jobs, family and school, so they rarely spend time on campus after classes are over. If campus life is an important part of the college experience for you, look for a community college that offers campus housing or plenty of extracurricular activities. These features will give you a sense of the college community you are searching for.

- Can I get a job with an associate degree?

According to the American Community Colleges website, the answer is a resounding “Yes!” One recent study found that Americans with associate degrees had a 24% share of “good jobs” in the economy (defined as defined as one with an annual salary of at least $35,000 for those under age 45 and at least $45,000 for workers age 45 and older).

- Can I transfer to a four-year school?

If a four-year degree is still in the back of your mind, look for a community college that has a transfer agreement with a four-year school in your area. These transfer agreements ensure you can move all your credits earned in community college toward your four-year degree program. In some cases, counselors work with students directly to ensure the courses they take at the community college level will be the best contributors toward their eventual four-year degree program.”

– Passage from College Board

Applying to a Community College

Focus Questions:

- Is it possible a community college might have scholarships for which international students are eligible?

- Is it possible that an international student might work in the US for a period of time after graduating from a community college?

Unlike most four-year colleges and universities, many community colleges do not require international students to take standardized admissions tests to gain admission. Many require that they take an English proficiency test, and/or an English placement test upon arrival for proper course placement. In addition, many have rolling deadlines for admissions.

These are some of the other requirements they may have:

- Application fee

- Bank statement (check with individual college for required amount)

- High-school diploma or high-school equivalency, and possibly academic transcripts from all institutions ever attended

- TOEFL scores (check with individual college for required score) or other English-proficiency test scores

- Copy of passport

Application procedures, deadlines, and start dates will vary greatly among individual community colleges. In addition, there may be program-specific requirements.

In many cases, consultation with the individual community college will determine whether the student should apply first to an Intensive English Program (IEP) delivered within the school or straight into the certificate or degree program. This will depend on student goals as well as English proficiency.

There may be institution-specific scholarships available at some community colleges, staggered payment plans, and if an international student is doing well at a community college, they may go on to receive a scholarship at a four-year institution.

In general, international students should apply at least three months before the start of a degree or certificate program session and at least two months before the start of an IEP course.

Some international students may find on-campus jobs where they can work for up to 20 hours a week, but these are limited. In addition, students may apply for permission, while studying, to remain in the US for a year after they graduate to obtain work in their field of study. For more on work options for international students, please see Section 12.

Colleges and Universities

In this section, we outline the broad scope of educational choice at American colleges/universities – please see Section 6 on two-year colleges and Section 5 on CTE schools as well.

For many years and especially in some countries, there has been a perception that the best universities in the US are in the Ivy league, a group of prestigious private institutions, or other large and well-known universities, but this is not always the case. Many less well-known colleges have excellent programs and can be the exact right fit for a student.

Agents should be sure that they are aware of the strengths and benefits of a broad range of options for the students they work with.

Focus Questions:

- When a university has the term “national” in it, does it mean it is overseen by the national government?

- What is the difference between a private and public university?

The American university system is diverse. Over 4,000 degree-granting institutions deliver a wide range of programs offering unique experiences for international students.

Part of the reason the higher education landscape is so diverse is that, as mentioned in Section 2, the federal government is not involved in recognizing educational institutions, programs or curriculums, or degrees or other qualifications. The education system is “decentralized” as a result: state governments are responsible for overseeing the activities of higher education institutions.

Within the overall university system, there are public universities and private ones.

Public Universities

Most public universities are operated by the states and territories, usually as part of a state university system (which is a group of public universities supported by an individual state). Each state supports at least one state university and several support many more. California, for example, has an 11-campus University of California system, a 23-campus California State University system, and a 109-campus California Community Colleges System.

Local cities and counties may also support colleges and universities.

The federal government manages only the five “service” academies (Army, Navy, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine) that are public; there is no “national” university.

It is very important to understand, therefore, that the use of the term “national” in a university names does not indicate federal support or stature. For example, National University of San Diego, California, is a private university. Similarly, the use of a state or city name does not automatically imply that an institution is public. Murray State University is a public university; the University of Pennsylvania, by contrast, is a private institution.

Public universities are often larger and are often less expensive than private universities.

Private Universities

Private colleges and universities are those that do not receive their primary support from the government. Among these, some are secular while others have a religious affiliation (e.g., Roman Catholic, Judaism, etc.). In general, religiously affiliated institutions welcome students of all faiths, and religious courses are minimal or optional.

Private institutions are either non-profit or for-profit. For-profit institutions are often more focused on careers and technical education than academics.

The University of Phoenix is a prominent example of a private, for-profit institution. Private universities are often more expensive than public ones, but they sometimes have more financial assistance set aside for international students.

Whether they are public or private, US colleges and universities vary in terms of what their overall focus is.

Some emphasize a vocational, business, engineering, or technical curriculum; others emphasize a liberal arts curriculum. Many institutions combine some or all of the above.

The Undergraduate Journey

Focus Questions:

- What is a “major”?

- How many credit hours, in general, must students complete in order to receive a bachelor’s degree?

- How many credit hours are most college courses worth?

- What is meant by a “cumulative GPA”?

Four-year colleges and universities specialize in bachelor’s degree programs and some also have a graduate school attached to them for master’s degrees.

It generally takes four years to earn a bachelor’s degree in the US. Each year has a word associated with it to easily identify the student’s academic standing: Year 1 = Freshman, Year 2 = Sophomore, Year 3 = Junior, and Year 4 = Senior.

Most undergraduate programs require that students take courses – sometimes called pre-requisite courses – across several disciplines (for example, literature, history, science, the arts) before they specialize in a “major.” These initial courses are meant to create a foundation for more specialized study within a degree program, and they are aimed at producing well-rounded graduates with more than just specific knowledge.

The focus becomes more specialized with each year of study, and post-graduate and professional programs (see Section 8) programs are the most specialized.

At the start of their third year of study (their Junior year), students declare a major (the main focus of their study in a degree program). Two examples of majors: A Major in Anthropology as part of a BA program, a Major in Biochemistry as part of a BS program. To complete their degrees, students must take a certain number of courses within their major focus.

There is also an option to declare a “minor” as well as a “major.” Coursework in the minor is often complementary to what the student is learning in their major – it tends to be at least somewhat related. For example, a student could take a human resources management major and a minor in psychology; the minor complements the expertise the student will obtain in their major.

Credits and Grades

Focus Questions:

- How many semesters does it normally take to complete a bachelor’s degree?

- What kinds of methods are used to evaluate students in order to assign them grades?

- What is a cumulative GPA?

In most cases, bachelor’s programs require that students complete around 125 credit hours of coursework. Given that it usually takes students eight semesters (four years) of study to complete a bachelor’s degree, the average course workload per semester is approximately 16 credits (which equates to five or six classes).

To be considered a full-time student (which international students are expected to be), one would have to pass a minimum of 12 credit hours per semester for undergraduate programs and 10 hours for post-graduate programs. Most college courses are worth three credit hours, though they can sometimes be less or more than this, depending, in many cases, on whether the student is expected to spend less or more time on the course than usual.

A typical three-hour course would include lectures, class discussion, readings, and possibly field trips or other activities designed to maximize the experience and value of the course. Evaluation methods may include any or all of final exams, mid-term exams, term papers, and other assignments. In most cases, exams can only be taken once, so students have to study well to pass the course.

There are generally five grades – represented by letters – students can receive in their college courses, and each of the letter awards the student different points per credit hour that are then part of the calculation for a student’s GPA (grade point average):

- A is the highest grade (4 points)

- B means the student did above average in the course (3 points)

- C is the average passing grade (2 points)

- D is the minimum passing grade (1 point)

- F means the student failed the course (no credit, zero points)

Students receive a new GPA every semester, but every course the student has taken toward completing their credential is reflected in it (in other words, GPAs are cumulative, so will reflect past semesters as well). A perfect GPA would be 4.0, and it would mean the student had achieved an “A” in every course completed.

Of course most students do not achieve perfect GPAs. Here is an example we found of a lower GPA, where the student passed five courses worth different numbers of credits and achieved varying grades:

- Chemistry 101: 4 credit hours, grade of B = 12 points)

- English 127: 3 credit hours, B = 9 points

- Sociology 111: 3 credit hours, C = 6 points

- Astrophysics 101: 5 credit hours, D = 5 points

- Music Appreciation: 3 credit hours, A = 12 points

- Total credit hours passed: 18

- Total grade points achieved: 44

- GPA for this semester: ca 2.4 (total points divided by total credit hours)

In the above example, you can see how the GPA was lowered by the C and especially the D.

As a student progresses through his or her studies, the student develops a cumulative GPA, which is their overall grade point average across multiple semesters.

Each institution will have various cut-off points for required GPAs for students to remain studying at the institution. For example, first-year students with GPAs of lower than 1.8 would likely get put on academic probation at many institutions, and if it were lower than that, they might be expelled (asked to leave the school). Every institution will have policies about the GPA required to be eligible for scholarships, applying to a graduate program, and being on the Dean’s List (also known as an Honor List for high academic achievement).